How Red and Blue Product Design Shapes a Market

Every product makes a first impression, whether it’s a car, software, or spice container. Customer worldview shapes that impression because product design reflects social truths, which are distinct between liberal and conservative customers. How social truths align with each group from a product design perspective is a source of improved business optimization and market efficiency.

Product design reflects many inputs, not all from the customer, market research, and competitive analysis. The CEO typically makes the final call on important decisions representing the face of the business to the market. This often includes reviews of brand identity, product design, and advertising concepts.

If the CEO is a founder-CEO, the decisions are more personal as their identity is tied up with the business's identity. When these design decisions are made, the business sets course into a market with design potentially calibrating the addressable market along conservative-liberal lines, for better or worse.

Does product design with a liberal or conservative expression only appeal to more liberal or conservative customers? No, for three reasons:

First, expression of worldview is thematic, not deterministic. In other words, it’s an underlying signal that may be strong or weak. Second, product value, quality, and performance can overwhelm an underlying worldview signal to bridge the market. Third, markets aren’t always binary with regard to conservative and modern design concepts. Superposition can take place. For example, some liberal customers will appreciate traditionally designed products and vice versa.

Despite these three qualifications, product design represents an opportunity for stronger alignment with the market to support greater efficiency in customer acquisition and value. When product design makes the right first impression for the right audience, efficiency follows. The idea is to be aware of your market’s worldview and compare it to that of the business.

Characteristics of Red and Blue Design from Social Anthropology

In a previous article, I applied the work of social anthropologist Mary Douglas, in developing a model for how American conservative and liberal customers think. In a nutshell, the model has a foundation of Individualism across both groups, a core attribute of the American Dream. Conservative customers then apply a Positional filter to Individualism, and liberal customers apply an Egalitarian filter.

So both groups have a common foundation, while conservative customers moderate Individualism with tradition and hierarchy. Liberal customers moderate Individualism with the idealism of the collective and shared social values. See the other article for a more detailed exploration of that model.

To see how the model plays out in product design, let’s first consider the relationship between the two groups and the idea of what is “modern.”

“Modern” in a very general sense refers to a break from tradition. Modernism is a movement born out of the industrial revolution, which transformed an agrarian economy into one of industry and machine manufacturing.

Along with that transformation came enormous shifts in population: In 1800, only 6% of Americans lived in towns larger than 2500 people. By 1920, over half lived in cities, relocating to new opportunities. As a result, modern life became associated with urban life, especially when there is a focus on change and “progress.” As French social scientist Emile Durkheim commented about living in cities, “Minds are there oriented to the future.”

The demographics of liberal customers today certainly indicate a more urban location, along with inner suburban communities. Conservative customers are primarily found in less-dense areas, especially outer suburbs and rural areas. Population density is correlated to the presence of liberal and conservative customers.

If urban liberal modernism reflects a break from tradition, then exurban and rural areas reflect more of a reaction against modernism and an affinity for less change. The roots of more rural and exurban areas are in groups who chose not to move to a more urban environment to participate in rapid change.

Embracing change is clearly reflected in modern art, where the rejection of tradition - realism - is replaced by exploring new ideas - abstraction, new processes, and using new materials. Modern product design follows suit, yielding more simplified, abstract forms rather than relying on complex, hierarchical ornamentation. Modern product design can also reflect a focus on newer materials and processes.

These are enormous generalities, but we need simple concepts to understand how markets align with products or not. We’re not trying to be experts in history or political science. Instead, we want to extract central ideas and apply them in a business context for growth.

It’s no coincidence that a similar sensibility exists in social anthropology. As Mary Douglas commented, “One of the objections of art historians to the approaches of anthropology and sociology is that we oversimplify. Yes, we do.”

Product Design as a “Banner in Cultural Context”

In Mary Douglas’ book Thought Styles, she explores the relationships between different social groups and design sensibilities. She refers to the more liberal Egalitarian group as “entrepreneurial.” She comments that this group “needs to brush aside the formal trappings of the currently established regime, so those people are not against all decoration so much as against that which they regard as effete and overloaded, the style currently preferred by the present hierarchy. They need space for their innovative lives and are against irrelevant clutter.”

So when you hear someone state that they like “clean, uncluttered design with lots of white space,” they are most likely expressing alignment with a more liberal urban culture. Many technology companies or “modern companies” certainly express themselves to the market this way in product and communications design. It’s not a problem unless the product predisposes itself to the other half of the country or you want to maximize the size of a national addressable market.

Douglas does not promote one group over another, referring to the different design sensibilities of social groups as “competing streams of taste and value.” Instead, she states, “To know what is happening to taste, we need to trace its manifestations over a whole range of objects, recognizing them as banners in cultural context.”

So there is no right or wrong here. Instead, it’s a matter of sensibilities of different social groups, with product design acting as a “banner” signaling to membership of a particular social group, which in our case are American liberal and conservative customers.

Now let’s look at some products and their design to evaluate them as “banners in cultural context.” Along the way, we’ll see that it’s often more complicated and interesting than what first appears because conservative and liberal customers have many different attributes.

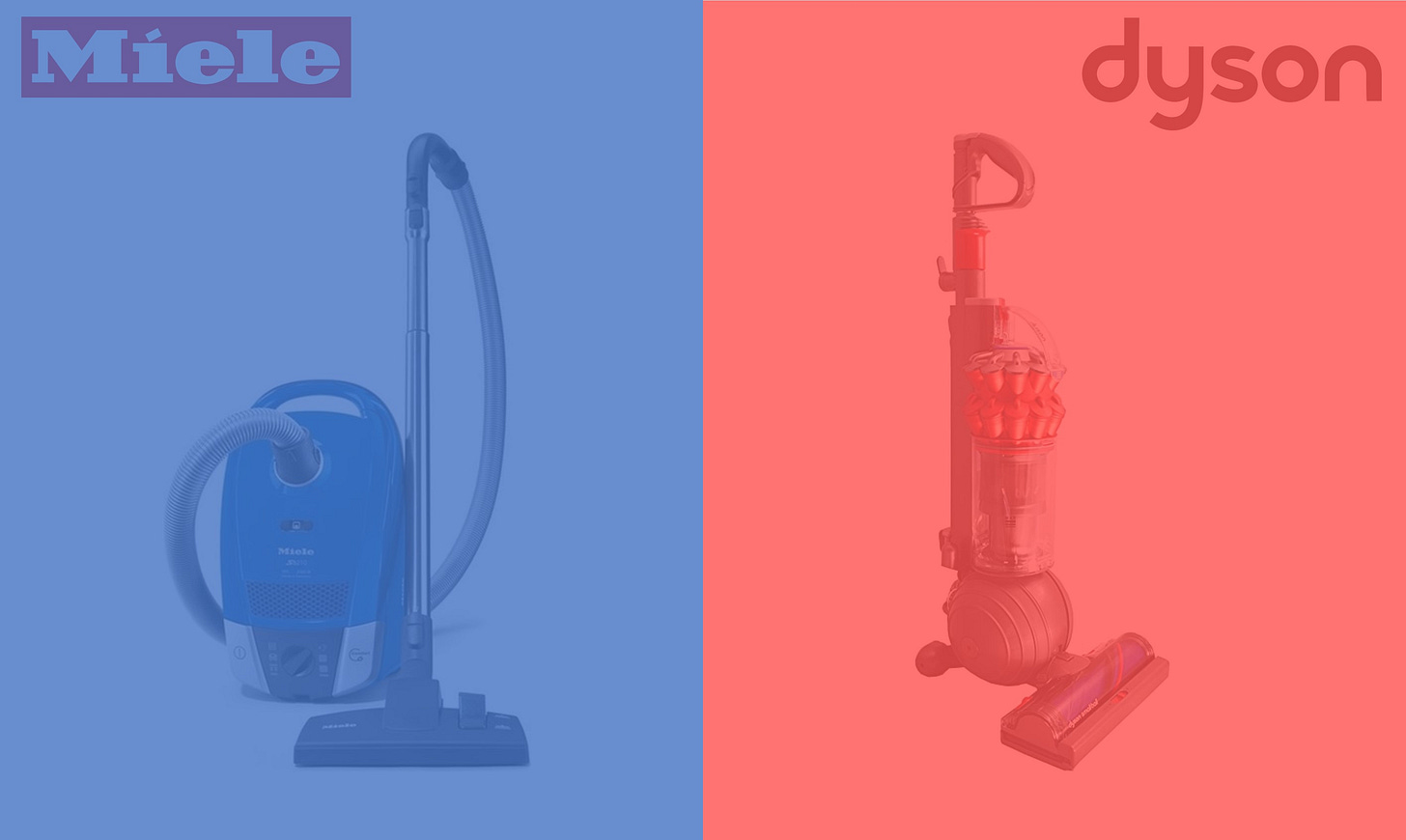

Miele & Dyson: Engineering Overcomes Potential Worldview Perception

On the face of it, the Miele vacuum cleaner has more modern liberal design signals while the Dyson product has conservative signals. The Miele is devoid of decoration, favoring abstraction and empty surfaces. The Dyson offers intricate detail and lots of decoration, looking almost cathedral-like. If you wanted to invoke iconic architectural comparisons, you might use Mies van der Rohe’s Seagram Building and the Duomo in Milan, an actual cathedral.

Both products serve the same function, take up the same amount of space, and are priced at a premium. Yet it’s easy to see how the two products will make different first impressions. Once customers learn more about the products, they may choose one from across a worldview divide based on such attributes as quality, value, and capability.

Dyson products represented breakthroughs with higher performance than many competing products, appealing to a big audience, liberal and conservative. Dyson’s engineering capability and performance serve as a counterpoint to its decoration and hierarchical impression.

James Dyson, the billionaire founder of Dyson, clearly has an outsized influence on his product design. He initially studied furniture and interior design before switching to engineering. While at the Royal College of Art, he focused on industrial design. He applied the principle of cyclonic separation to vacuum cleaners where there is no loss of suction as dirt is picked up, resulting from frustration with his Hoover. The result was a blockbuster success.

The Dyson design reflects an engineering mindset, showing off all the innovation. Innovation can be seen as a more modern liberal signal if it pushes a break from tradition. But in this case, the customer is not being asked to do anything different. The product does not require any new behavior to take advantage of the innovation.

Perhaps this combination of having forward-looking technology, an innovation that is not disruptive, and decorative-mechanical features contribute to more mass appeal. However, at first glance, it looks anything but modern in terms of a design aesthetic.

Dyson is characterized as conservative, serving as a huge supporter of Brexit. Yet he also garnered an apology from the BBC for having characterized him as such for contributing to an engineering festival. It may be pure coincidence, but when he moved the Dyson headquarters to Singapore, he chose a building that was a former power plant, the design of which is hierarchical with, um, a history of power, a core attribute of the Positional social group.

Tesla & Ford: Easy Assumptions at First Glance, More Interesting Than It looks

According to a research report from Strategic Vision, as reported in Forbes, the Tesla Model 3 over-indexes for liberal customers while the Ford F-250/350 over-indexes for conservative customers. At first glance, it’s easy to see the correlation relying on a stereotypical reaction. However, it’s far more interesting than that.

First, the Tesla Model 3 clearly reflects a modernist sensibility from a product design standpoint. This is about as abstract a car as it gets. There’s no grill on the front, and all details are minimized, blending into the car's body. Even the door handles disappear as if they are unnecessary decorations.

The Ford F-250, while not highly decorated, is muscular and strong, playing into the Positional preferences of the conservative customer. That’s the simple analysis - one based on an immediate first impression of product design only.

Where this gets interesting is in the fact that Tesla, as a brand, ranks number four for conservatives in brand reputation. Wait, what?

If you spend time in very liberal San Francisco, you know you can’t fall down without hitting a Tesla on the way. They are everywhere. Tell someone in San Francisco that Tesla ranks high with conservative customers, and you will get a confused, stunned reaction. After all, it’s an EV, it’s innovative, it’s modern, it’s forward-looking - it absolutely breaks from tradition.

There are a few potential explanations if you look through a lens of social anthropology for Tesla, as well as Apple (also ranking high with conservative and liberal customers in the same study for brand reputation).

Like James Dyson and his vacuum cleaners, Tesla cars represent an engineering feat. Tesla redefined what an EV can be, and the brand continues to dominate the EV market. The misconception of conservative customers is that they won’t adopt disruptive, innovative products. Of course they do, but in their own time, when they are proven, without all the experimentation with the bad products.

By the same token, Apple would never be as successful as they are without conservative customers. Early urban liberal adopters pave the way for conservative customers, both working together to create larger markets.

The other explanation, which can be a little controversial, is status. Few people want to admit to making any purchase because they want to evoke status.

Tesla is an emerging luxury brand. Even the “low end” Tesla Model 3 costs some sixty to seventy thousand dollars while other models are well over a hundred thousand. It doesn’t yet appear on a ranking of luxury brands, even though Porsche, Ferrari, and other car companies do.

Luxury brands evoke status, and liberal and conservative customers have their versions of status. For liberal customers, status is social status. For conservative customers, status is positional status. Think of it as prestige vs. power. Both relate directly to the Egalitarian and Positional social attributes developed by Mary Douglas. Luxury brands are unique and powerful because they can appeal to the wealthiest people in both worldview groups, creating the largest possible high-income market.

Airstream: A Quirky Traditional Modern Design for National Exploration

Airstream trailers seem to have universal appeal. The sleek yet retro look brings smiles to many faces. The design has not changed that much since the 1930s and 1940s, making it modern in its sleekness and traditional in its cues as a product from another era. It uniquely bridges the design sensibilities of the two worldview groups in an instantaneous, simultaneous way. Underlying all of this are also core American traits and an interesting split in the market itself.

Wally Byam founded Airstream in the 1920s after building a travel trailer for himself, which appealed to fellow motorists and friends who wanted one. He was a Stanford graduate who first worked in journalism, advertising, and publishing. He opened his first trailer factory in Culver City, California, in 1931.

Wally’s interests and decisions were prescient for a market about to explode. Joshua Levy, a historian at the National Archives, writes in a post, “The American road trip was first popularized during the auto-camping craze of the 1920s, with its devotion to freedom and communing with nature, but it was democratized after World War II. The golden age of the American family vacation came during the very height of the Cold War. It was a time when, according to historian Susan Rugh, the family car became a “home on the road… a cocoon of domestic space” in which families could feel safe to explore their country.”

Exploration is at the heart of the American psyche. According to a research report by Timetric, as covered in Traveller, the United States has the number two most traveled population globally, second only to Finland. Yet that travel is uniquely national, with only one in five Americans traveling abroad in 2013. It’s the exploration of the country itself, not an exploration of a disruptive idea, and within a national context. Airstream, and RVs in general, are a strong fit for the American public. But who are the customers, and in particular, for Airstream?

In a Harvard Business Review interview in 2003, then Airstream president and CEO Dicky Riegel commented that “Although there’s no clear Airstream buyer demographic, there are three distinct psychographics: design enthusiasts, traditionalist campers, who include what we call “retrofurbishers,” and value customers . . . A 30-year-old design enthusiast from New York and a 65-year-old retrofurbisher from Michigan can pull up next to each other at a rally and find they have a lot in common.”

When you look at the overall market for RVs, there is interesting evidence of a parallel split in the market. A research report released by the RV Industry Association (RVIA) indicates that 71% of the market for “fifth-wheels” - trailers that extend over the back of a pickup truck, have no children at home, and 18-34 year-olds make up 22% of the market.

When you combine a bifurcated market (younger-more liberal and older-more conservative) with bifurcated product design, you have very interesting intersections in product-market fit. The more liberal urban customers can even take an Airstream to go “glamping” and meet other glampers at such events as the one held in the town of Liberal, Kansas.

Worldview-Centered Product Design Oils Product-Market Fit

Few businesses have an easy time growing and achieving higher levels of profitability. Success comes from pulling many levers to improve product-market fit. Product design is one of them. Aligning product design with the market based on worldview doesn’t have to cost more. You just need intention from the start so that resources at your disposal are aimed in the right direction. It also requires self-awareness of how the business thinks from a worldview perspective to determine if there are any potential misalignments with how the market thinks.